I thought I knew what I was in for when my brother died. I’d lost friends. I’d lost grandparents. Cousins. Uncles. Being a “rainbow baby,” a child born after stillbirth, I honestly felt as if I was born into a culture of grief. Even my signature bears the weight of tremendous loss: my father’s brother and my mother’s sister inspired my name. I can’t even sign my name at the doctor’s office without being reminded of the deaths that had devastated both halves of my family so many years ago.

Even still, nothing could have prepared me for the sting of losing Nate. I remember the second my siblings and I received the news. It was five-something in the morning. All that my sister could manage to say was a simple, heavy-breathed: “He’s gone.”

The denial was swift and unforgiving. I wrote in a journal the day after we’d lost him that I couldn’t even stomach thinking the “D word” (read: dead). On the inside, I was in the process of breaking down entirely, though it wasn’t obvious to everyone. I had completely lost touch with my reality, opting to throw myself headfirst into my college coursework instead of dealing with the fallout of my brother’s untimely death. In my personal life, many people were noting how “well” I’d taken to grieving. They were applauding me for hiding my pain, and, to be completely honest, I was enjoying the positive attention.

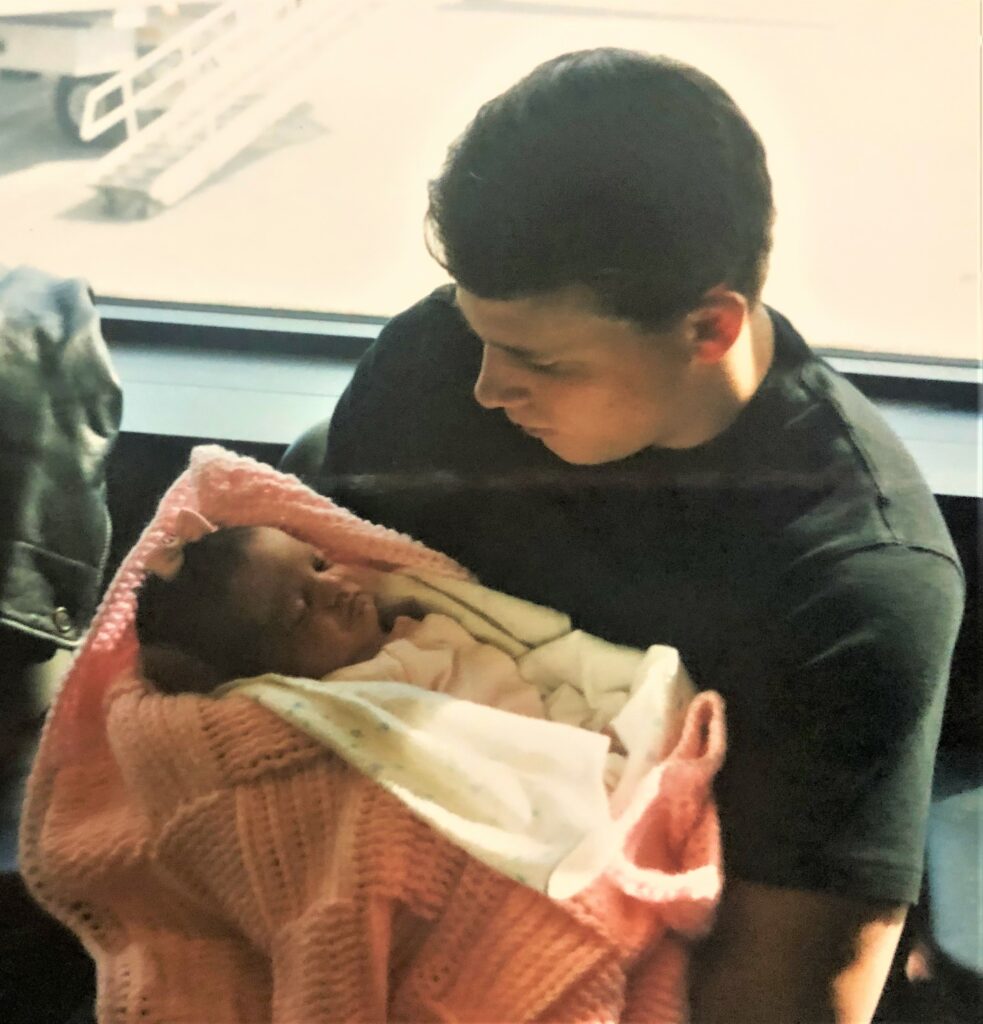

Nate holding Karly, 2021

“You’re like Superwoman,” I remember being told. “It’s spectacular.”

People were calling, texting, even visiting me in person just to let me know they were here if I needed anything; however, at the same time this was happening, I was receiving so much affirmation that burying my feelings was the right—no, the strong—thing to do.

When the “seal” broke

Then, two months later, it happened. The seal with which I was holding my grief back finally exploded under the pressure. I fell deeply into the spiked pit of bereavement, and I saw no way out: I was unable to leave my apartment. I couldn’t eat, shower, or brush my teeth. I was struggling to perform even the most basic of tasks, functionally glued to my bed and condemned to lose myself in the endless Tiktok algorithm for hours at a time. It was my partner who finally pointed out that I needed serious help, so I decided to cancel all of my plans for a week in order to focus on re-grounding myself. I was sure it was the right move, but when I reached out to cancel plans and make arrangements for alternative assignments at school, I wasn’t quite met with the same compassion that I’d received just two months earlier.

“How long are you going to use that as an excuse?” One friend asked me over canceled dinner plans.

“His death wasn’t particularly violent, though,” An educator said.

“You sure know how to kill a vibe,” I was told by a loved one after crying at coffee.

Slowly but surely, these remarks became my new normal. The polite but often flat apologies I’d been hearing were replaced by comments that I felt were urging me to just get over it. The truth is, though, that the death of my brother is something I will never “get over,” and no amount of shaming me for grieving will change that.

The Jacklin family in 2019, Karly being held (Nate 3rd from left)

Recently, I shared a post on social media about how much I missed Nate, and it was reported. I was confused as to why a post like that would be in violation of Instagram’s guidelines, until I was made aware that it technically wasn’t when I received a notification that read: “someone thinks you could use extra help right now and asked us to help.”

I wasn’t angry with any of my social-media followers, but the experience of having my grief deemed disturbing enough to warrant reporting was enough to make me recognize a larger problem: most people, while very well-meaning, have no idea how to interact with the bereaved.

Grief calls for learning to adapt, not “getting over it.”

Our culture is scared of mourning. It makes us uncomfortable to see the ones we love in pain, and our immediate reactions often include figuring out how to stop the pain entirely. But, as stated earlier, grief—especially complicated grief—isn’t something that the bereaved can just stop feeling. So much of the grieving process is learning how to adapt to living with the pain, not learning how to stop it. Establishing a new normal without Nate was the hardest thing I’ve ever done, and I’m sure it will stay that way for a long time.

The good news is that grief doesn’t have to derail your life forever, and that’s where community support—not shame—comes in. I asked fellow grievers what helped them the most through their own unique struggles, and every single person I met with mentioned having someone listen to them without judgment.

Compassion and empathy for the bereaved can flick an invaluable light on inside some of the darkest times we will ever know. Every single experience of grief is different, but nobody who is in mourning appreciates being shamed. We’d like for you to sit with us when we cry.

What we crave

We’d like for you to ask us questions about the interests and the quirks of our loved ones. We’d like for you to still be there for us, even after the “socially acceptable” window for grief has passed. I promise you, ten years later, we’ll still be missing our people just as much as we were on the day they died. If you’re still not sure how to support the mourner in your life, just ask. How could you know the right thing to say if you don’t know what it is?

About three months after Nate’s passing, I was having a particularly rough day.

“What can I do to help you?” My partner asked.

I thought for a moment, before answering teary-eyed and in all honesty: “You can get me a bagel.”

No, sesame seeds and cream cheese didn’t fix everything, but it made me feel loved and supported during a terrible time, which is why it was probably the best bagel I’ll ever eat.

Karly Jacklin is a poet and essayist living in western Maine with her partner and a little grey cat. She’s on threads at @karjacklin, and her full portfolio can be found at karjacklin.carrd.co.

Beautiful tribute and a reminder for all of us to LISTEN and offer support that is as individual as the person grieving ❤️

I am so grateful that I read this article. My 40 y/o son died 4 1/2 months ago. I’m afraid people want me to be over “this”. And I feel so validated by reading this. The fact is I’ll never be over it. It’s changed the fabric of my being and is now a part of me.

Dear Marsha, you will probably always miss your boy. My son died four and a years ago at age 33. He had been quite ill so it was expected, but it still hurts. I would not wish him back here in his sickness, but I do miss him. I often tell him good night at the end of my day. And we celebrate his birthday with his favorite ice cream. I wish you peace.