As children return to school they do so with a myriad of experiences and personal stories that may have happened over the summer or longer ago. For many children–approximately 6 million, according to the Childhood Bereavement Estimation Model–those experiences include the death of a parent, caregiver, and/or sibling. (That number doesn’t include children who have experienced the death of a grandparent, cousin, aunt, uncle, or friend.) Grief is considered to be everything one thinks, does and feels after the death of someone important to them or after a loss.

It’s important to know that grief can present in ways that are similar to plenty of other life experiences–including, commonly, having Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). When it comes to ADHD and grief, this is important because ADHD is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders of childhood. It’s usually first diagnosed in childhood and often lasts into adulthood. Children with ADHD may have trouble paying attention, controlling impulsive behaviors (may act without thinking about what the result will be), or be overly active.

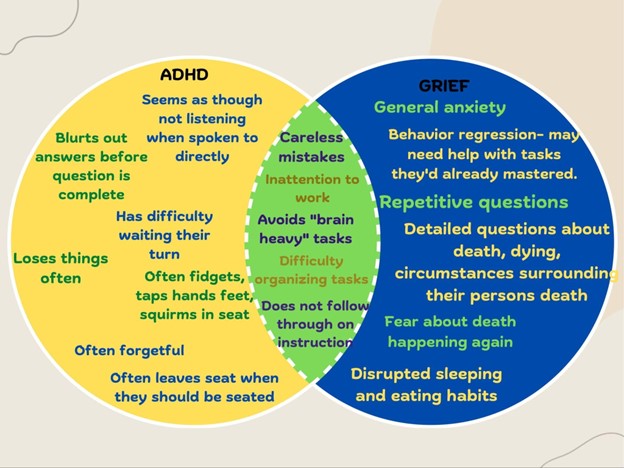

When it comes to ADHD and grief, there is a lot of crossover in behavior.

Why ADHD and grief are often confused

Let’s start with symptoms you may see: You may notice that a child in your care is having trouble focusing on simple tasks, is frequently making careless mistakes, often seems like they are not listening when spoken to directly, and seems to need constant repeating of instructions. A child may have difficulty remembering when you ask them to do things and struggle to keep up with multi-step instructions. You may also notice that a child does not sit still and often fidgets with their hands or taps their feet. They may blurt out answers to unfinished questions, struggle to stay quiet, and find it extremely hard to stay seated in situations where it is expected of them.

Lack of ability to focus

While these are all symptoms of ADHD, some of these are also symptoms of grief. In the same way a child with ADHD may have trouble focusing, a grieving child often will too. When stressful events occur–such as death or other losses (immigration-related, caregivers separating or getting divorced, changing schools, the foster care system, incarceration, etc.)–our brain’s ability to navigate events is pushed past its limit. Some stress is healthy, it helps our brain grow; other stress can become chronic stress which has an impact on the trajectory of our brain’s growth.

Note: Grieving children are at risk of chronic stress, and this chronic stress releases hormones into their brain that impact their ability to access the part of their brain required for cognitive functioning. Put simply, a big scary thing happens, and the brain goes into survival mode by releasing certain hormones. If that stress isn’t adequately addressed these hormones then can impact a child’s ability to do the very thing required of them in a class: focus.

Sleep issues

These same hormones can disrupt a child’s sleep pattern, and a common grief response is dreaming (or having nightmares) of the person who died. Many grieving children are coming to a classroom without adequate sleep. Even without the grief interfering, we know that adequate rest is important for young brains. These children may avoid brain-heavy work, which may look like not listening, not completing assignments, and zoning out in a classroom. It can also look like talking a lot in a classroom.

Sadness, anxiety, and other feelings

Also, grieving children feel many different feelings including sadness, anger, fear, happiness, confusion, and worry to name a few. We know that feelings can manifest in the body. Anxiety might be the constant tapping of feet or playing with hair. Fear can be a palpitating heart or using the bathroom every five minutes. Sadness might be crying, sadness might also refusing to talk to anyone.

It helps to know that grief responses are often different than ADHD symptoms in that they can include crying a lot, getting clingier, disrupted sleep, becoming more concerned with their safety and the safety of others, worrying about being left or abandoned, complaining about headaches and stomach aches, regressing, getting reckless (using drugs, alcohol, and unsafe sex practices) and thinking about suicide or self-harm.

What to do if you’re seeing these symptoms

It’s hopefully clear now that it can be hard to tell the difference between ADHD and grief. If you find that you are noticing some or many of the symptoms above, here are steps you can take.

1. Talk to caregivers about any big changes in a child’s life. Teachers and health practitioners should check in with caregivers about big changes in a child’s life and remember that death is not the only thing a child may grieve. This collaboration increases a child’s chances of accessing support.

2. Talk to children directly about big changes. Even if a child is not ready to talk about it or doesn’t understand the change yet, when adults make time to start the conversation, it sends the message that someone cares. It reminds children that they do have support. Here’s a possible conversation starter: “Tell me how your summer was? Did anything big, exciting, or even scary happen?”

3. Reach out to grief and ADHD professionals. You do not have to be the expert. You can advocate for the child(ren) in your care by accessing professionals who are trained in these topics. Make time to connect with your local children’s grief centers. ADHD testing is also available if you have confusion or concerns. Caregivers can access testing by speaking with their child’s primary care provider or working with their child’s school psychologist to begin the process of accessing ADHD and other mental-health related tests.

Lastly, in addition to school counselors, check in with psychologists and therapists for more support. Not only can they collaborate with you to support your child(ren) in school, they can connect you to services and support outside of school.

Want to know more about ADHD? Visit:

- National Institute for Mental Health: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

- American Psychological Association: ADHD

- Centers for Disease Control: Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

- Eye to Eye (a nonprofit created for and by people with learning disabilities)

Want to know more about grief? Visit:

- Uplift Center for Grieving Children: Tip Sheets

- Experience Camps Grief Resources

- Developmental Responses to Grief from the Dougy Center: The National Center for Grieving Children and Families

- Judi’s House for Grieving Families and Children: Childhood Bereavement Estimation Model

If you’d like to learn more about the really scientific parts of grief and the brain you can visit

- Grief: A Brief History of Research on How Body, Mind, and Brain Adapt by Mary-Frances O’ Connor

- What Does Grief Do to Your Brain?

Samantha Anthony is a grief clinician who operates out of Uplift Center for Grieving Children in Philadelphia. She has lived in the USA for 11 years after immigrating from Malawi. She has an M.S in Clinical Child Psychology and a vested interest in the interconnected areas of childhood mental health, with special focus on grief, trauma, social justice, and education.

Samantha Anthony is a grief clinician who operates out of Uplift Center for Grieving Children in Philadelphia. She has lived in the USA for 11 years after immigrating from Malawi. She has an M.S in Clinical Child Psychology and a vested interest in the interconnected areas of childhood mental health, with special focus on grief, trauma, social justice, and education.